An apocryphal story has it that a White European is in a small village in Africa and sees a group of local children. He wants to interact with them and give them something fun to do, so he says through his translator,

“Let’s play a game. You all race to

that tree over there, and the winner gets this bag of candy.”

What happens next surprises him.

Instead of racing each other to the tree, all of the children join hands

and run together. They all get to the

tree at the same time. The man is

puzzled as to who deserves the candy but the children explain, “We all won so

we can share the candy!”.

This story describes the basic tenets of the Ubuntu philosophy: «I am because we are» and “humanity towards others”. The tale can be read in different ways, of course: a kindly gentleman playing with children; a White European man trying to impose his “superior” ways on an African community of children who already know exactly how they like to play; an honest misunderstanding based on a clash of cultures, etc. However, in this book, I would like to take this story to validate a different way of defining “game”.

With the “globalization” of our worldview, most people in the world

nowadays share a cultural background more in common with the European man in

the story than with the African children, at least where games are

concerned. This means we tend to define

games as in the definitions above: there must, at the very least, be recognizable

rules, goals and some sort of win/loss end-state. This assumption is clear in the story. The man had a certain pre-defined concept of

the meanings of words like “race” and “win”, so he assumed that each child

would run individually and that one would necessarily reach the tree

first. The children seemed to agree that

“race” means “run as fast as you can” but they obviously interpreted the

pronoun in the plural as in “as fast as we all can if we join hands”. They also interpreted “win” very differently;

in their view, there is no limit on how many people can win because whoever

fulfills the condition of running to the tree is entitled to some of the candy.

This begs an interesting question to which the story offers two seemingly

irreconcilable answers: what does it really mean to win? According to the man’s worldview, each child should

aim to maximize the amount of candy they get, so it would logically be in the

interest of each to run faster than the others in order to get all of the

reward. From the children’s point of

view, winning should make one happy, but one child cannot be happy eating candy

while looking at the faces of all her companions who have none.

This is not some sort of idealization of a so-called primitive or

child-like worldview, though the characters’ backgrounds may make it seem so because

of their respective ages and cultural backgrounds. Rather it is based on a firm scientific

understanding of the human brain in social settings and of how empathy is

activated through a phenomenon known as “mirror neurons”.

To illustrate, let’s look at another story, this one taking place in a laboratory at the University of Parma in Italy, where a neuroscientist named Giacomo Rizzolatti and his graduate students were studying a monkey with electrodes wired up to its brain. One of the graduates began to lick an ice-cream cone in front of the monkey. To everyone’s surprise, the exact same regions of the monkey’s brain showed activity as if the monkey itself was performing the action. A great deal of research followed this discovery, papers were published, and books written. Some of the books and articles produced outside of the academic realm were complete junk, of course, suggesting that somehow, we are all connected at these deep-down levels and isn’t it all groovy, man?

The science itself, however, is sound.

The “mirror neurons” exist to allow us to empathize with others. If you’re sad, you’ll bring me down; if I see

you stub your toe, I’ll wince. Babies in

a nursery with another baby who is crying will cry too. Rifkin calls this “empathic distress”. The point is that those of us who are not

psychopaths or otherwise psychologically impaired can feel what others are

feeling because we are social creatures.

“We are soft wired to experience another’s plight as if we are

experiencing it ourselves” (Jeremy Rifkin)

What’s interesting is that, as adults, we sometimes have to force ourselves

to deliberately turn this compassion off.

You simply can’t give money to every beggar on the street, you can’t let

your heart bleed every time you see images of suffering on the news, otherwise

you’ll drive yourself literally insane.

Children don’t necessarily filter their experiences in this way.

Empathy is a strong drive whose purpose is to enable us to belong to a group. Empathy in children is a value we can appreciate and encourage. Childhood is a special time of life where you shouldn’t need to live and die by the sword. Childhood should be a time for socialization through play.

Play is fun. But what makes playing a game fun for the players?

Richard Bartle defined four different “types” of players,

rather cutely matching them up to suites of a deck of playing cards:

- Diamonds refer to players who play to win.

They play by the rules and they keep the goal in mind every step of the

way. They expect other players to do the

same, so to them a good game is one where the players win or lose fair and

square.

- Clubs are players who don’t care so much about winning per se as about beating the other players. They often measure how much fun they had by

how much damage they caused to other players.

- Spades are the explorers. The rules and

goals of the game aren’t nearly so interesting as the game-world itself. They’re the ones who will often contribute

arcane knowledge to game wikis online.

They might not even play at all.

One player described his experience with Myst and Riven back when

they came out in the early and late 1990s respectively: he wasn’t at all

interested in playing the game, he just wanted to explore the beautiful sets,

opening doors and exploring game-world locations.

- Hearts are the socialisers. The game is

just an excuse to get together with people.

Jane McGonigal noted that a large demographic of people playing Words with Friends and other online and social

media-based games do so simply to stay in touch with loved ones, and that the

most common comments in the chat features were variations on “I love you, Mom!”

So, in a nutshell, what we have are roughly half of players (depending on the game genre) who don’t even care that much about winning, and even less about playing by specific rules or goals. This is amazing to me because it validates what the children in our story meant when they chose to run to the tree holding hands.

So let’s consider our littlest hearts and spades: our young children who

may prefer to use games as a tool for exploration or socialization rather than

competition.

Explorers might enjoy playing with the pieces outside of the context of

the game. They might want to make up their own games with them, or use

them to tell stories. Sometimes they might become interested in a

particular theme they were exposed to through a game and will want to read

books or watch documentaries that tie in.

Socialisers will enjoy playing with other people in a friendly,

non-competitive atmosphere. After all, from a child’s point of view, it’s

wonderful to spend time playing a game with a parent or relative who gives them

their undivided attention. Socialisers will also enjoy playing games

ABOUT people. Games about famous people or made-up characters invite

empathy, and a game centered precisely on making these game pieces happy will

feel fun and satisfying Ina different kind of way.

A game with these ideas is still a game in the sense that there are rules and goals and these are important for children to deal with. Free play is necessary and wonderful in its own right, but it won’t usually incorporate the math curriculum our children need to master as part of their education.

Yet most games involving math, whether they are deliberately

math-focussed such as Sum Swamp or Prime Climb, or whether they simply

happen to include math as a by-product such as backgammon or Monopoly, are

competitive.

I say we rethink what a game can be, and especially what a math game can be. Let’s consider children who are curious and empathic. Let’s consider parents who are, for whatever reason, math averse, yet want to play with their children. For these players, we can find a different definition of play.

In this blog, I define the parameters of the games in the following way: each game must involve math, it must arouse empathy through a theme, and it must consist of an interesting, yet easily made or purchased set of game pieces.

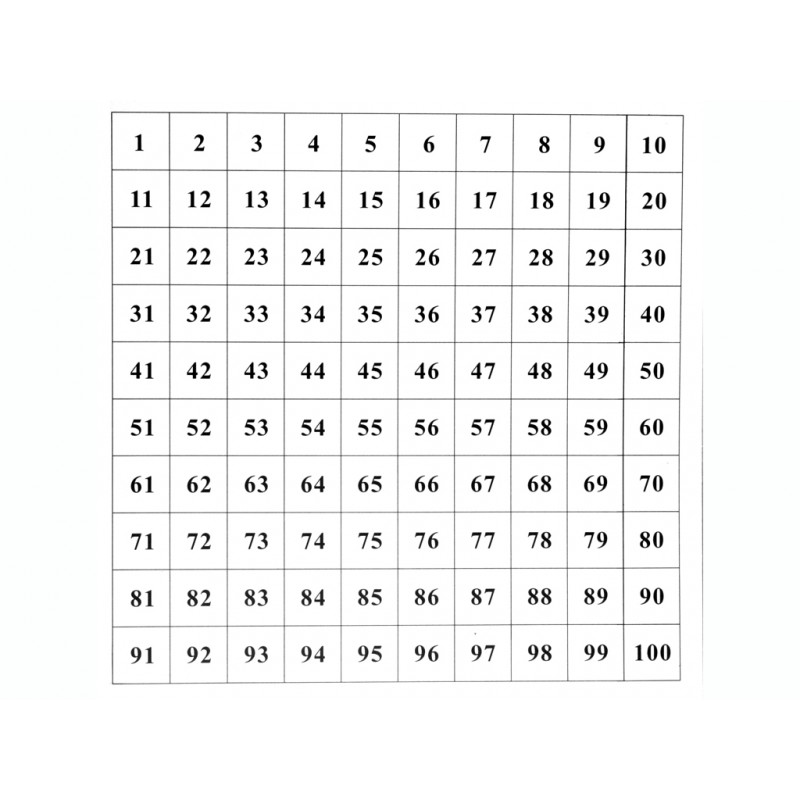

The math parameter involves teaching different concepts such as number

reading (the difference between 24 and 42, for example), subitizing (that 3+4

is the same as 5+2), sequencing, adding, subtracting, geometry, and other basic

math elements suitable for children aged 5-8. Each game will have a short

explanation of the type of math required and why it is necessary.

Each game must arouse empathy by having a theme. The theme can

involve fictional characters by having the players decide who should be on

which football team, it can arouse historical empathy by exploring the world of

real historical figures such as Sacajawea or Che Guevara, or it can simply be

based on the relationships between players. In this book, each game will

include a clear explanation of the theme, along with additional resources in

case your child wants to know more.

Finally, the pieces must be both easy to make (or inexpensive to buy),

and fun to play with. In fact, making them can be half the fun, as with

some of the card games or the ones involving paper dolls. Again, a

detailed explanation of the game pieces will be included, along with links to

templates or ready-made sets if they exist.

Each game will include a clear set of instructions and rules.

Within these, you and your child can feel free to explore the space of

possibility as you wish. Once you’ve tried the games as they are

described, you might have ideas for modifying them. You might play a game

once and decide you’ve gotten all there is to be had out of it, while others

can be played over and over.

The most important thing is to enjoy this precious time with your child

whether you’re a full-time stay-at-home homeschooling parent, or whether you

have just a few short hours a week to be together. Show your child that

math is fun and not to be feared. Show her that a little empathy goes a

long way. Teach her, bond with her, and above all, love her in the way

that only you can.